🗺️ Drawing the Line on a Map—and the World

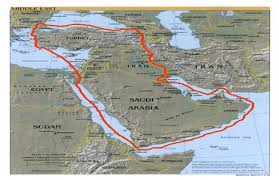

In 1928, in a quiet room at the Cannes Conference in France, a group of oil executives and diplomats gathered around a map of the Middle East. With ink and rulers, they drew a single red line—one that would come to define not only the geography of oil, but the early politics of a global energy empire.

This meeting led to what would become known as the Red Line Agreement, an extraordinary pact among five major oil companies: British Petroleum, Royal Dutch Shell, Compagnie Française des Pétroles (now Total), and two American giants—Standard Oil of New Jersey and Standard Oil of New York.

The red line they drew enclosed most of the former Ottoman Empire—including Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and parts of Saudi Arabia. Inside this vast zone, the companies agreed: no one would drill or develop oil independently. They would act as one. A cartel, by any other name.

🤝 Unity for Profit, Not for Peace

The stated goal was cooperation. The real goal was control. Oil was quickly proving to be the currency of modern power, and the companies—backed by their governments—sought to prevent competition, cap production, and lock down access across the most promising region on Earth.

This agreement allowed the firms to share risk and split profits. But it also ensured that the region’s native governments and rulers had little say in what happened beneath their own soil.

It was not just an economic alliance—it was a quiet act of economic imperialism.

🌍 The Empire of Energy Expands

The Red Line Agreement was emblematic of a new kind of imperialism—not through soldiers, but signatures. Western governments no longer had to occupy a country to control it; they only needed to control the contracts, the companies, and the crude.

This strategy allowed powers like Britain and France to maintain influence long after their formal empires began to wane. Meanwhile, the United States, whose direct colonial presence was limited, used its corporate might to begin carving out a seat at the Middle Eastern oil table.

The oil fields of Kirkuk, Mosul, and beyond weren’t just fueling economies—they were powering diplomatic leverage, military reach, and long-term strategic planning.

⏳ A Short-Term Pact, a Long-Term Precedent

Although the Red Line Agreement eventually dissolved—strained by shifting alliances and rising tensions—it left a lasting legacy. It formalized the concept of international oil cooperation, or more accurately, coordination to limit competition.

It also showed the world how deeply politics and petroleum had become fused. National borders were now commercial boundaries. Corporate rivalries mirrored diplomatic ones. And the people who lived on the land often had the least voice in how its wealth was used.

⚠️ Seeds of Resentment

To Middle Eastern leaders and nationalists, the Red Line was more than a corporate boundary—it was a symbol of exclusion. It fueled a growing realization: while the West extracted billions in profits, the region remained underdeveloped, its people underpaid, and its governments sidelined.

That resentment would simmer for decades, eventually erupting into revolutions, nationalizations, and a fierce rebalancing of power.

But in the 1920s and ’30s, the oil barons still held the pen—and the world was being redrawn, one contract at a time.